WARNING: Do NOT try this at home! The author is not liable for any damages caused by the wrongful use of the methods or ingredients mentioned in this article. But that’s all right, of anybody tries it, let me know, we can laugh together. (By the way, I wrote this post in response to requests by several readers made after the publication of “How Romans wiped their butts…”)

The first lights of dawn peek between the reddish roofs of the insulae and the marble columns of the temples. Fog is starting to break off from the ground, silently, ignoring the song of the first roosters, who do not care much for humans’ circadian rhythm and even less when celebrations are taking place in the Coliseum. We stand on the Vicus Patricius, one of Imperial Rome’s main arteries, which leads the way from the Forum towards the Pretorian Gate in the East. Just over the basaltic pavement, just when the cloud begins to take off, we see a pair of leather sandals erratically wandering under the feet of what it seems to be a man. It is a man, a soldier to be precise, judging by the numerous scars earned on the battlefield, cuts at an angle as long as a finger that time has turned into waxy memories on the skin.

Not without struggling, the legionnaire approaches a wall behind a metallic urn, some type of container or pot with scarce ornament, other than holders that simulate charging seahorses. We then hear a short splash, like the ones produced by flat stones thrown by children to the surface of a placid lake; then another, and another, until de cadence becomes a flow. The drunken soldier is relieving himself in a vessel next door to a fullonica, a laundry, where urine was used as detergent. Just like that.

Romans were very fond of cleanliness and we have already spoken about it in previous articles, the thing is that the concept of hygiene did not have the exact same meaning for them as it has  for us and we cannot criticize them for their habits because, as I always say, each civilization does what it can with what it`s at hand. And it was precisely the hand what our friend used to shake the last and precious drops from the urethra before marching stumbling back to the fort. A bit later, two workers of the fullonica, the fullones, brought the loaded vessel into a back yard, where there were half a dozen similar recipients. They had to let urine “rest” until it broke down into ammonia (NH3), a substance known for its pungent smell and that is still used in a large number of pharmaceutical and cleaning products. After a few days, the resulting liquid was mixed with

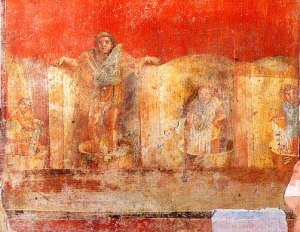

for us and we cannot criticize them for their habits because, as I always say, each civilization does what it can with what it`s at hand. And it was precisely the hand what our friend used to shake the last and precious drops from the urethra before marching stumbling back to the fort. A bit later, two workers of the fullonica, the fullones, brought the loaded vessel into a back yard, where there were half a dozen similar recipients. They had to let urine “rest” until it broke down into ammonia (NH3), a substance known for its pungent smell and that is still used in a large number of pharmaceutical and cleaning products. After a few days, the resulting liquid was mixed with  water to wash the noble’s clothing as well as garments recently out of the factory, since newly manufactured wool requires a washing process to eliminate some impurities and to make it softer. The job was done by hand, or better said, by foot, because the fullones used their lower extremities to stir and shake the clothes inside a container, something that the Spanish philosopher Seneca described as the saltus fullonicus and which reminds me the ritual of crushing grapes to make wine. Thereafter, the garments were rinsed to eliminate any foul smells and hung in an open space to let them breathe and dry. Sometimes a basket full of sulphide was placed underneath so that the gases aided in whitening the clothes.

water to wash the noble’s clothing as well as garments recently out of the factory, since newly manufactured wool requires a washing process to eliminate some impurities and to make it softer. The job was done by hand, or better said, by foot, because the fullones used their lower extremities to stir and shake the clothes inside a container, something that the Spanish philosopher Seneca described as the saltus fullonicus and which reminds me the ritual of crushing grapes to make wine. Thereafter, the garments were rinsed to eliminate any foul smells and hung in an open space to let them breathe and dry. Sometimes a basket full of sulphide was placed underneath so that the gases aided in whitening the clothes.

As it happens now, the fullonicas were liable for the proper care of the togas and, if any were damaged during the washing process, the owner had to pay a compensation. Still, the fullonicas were a good business, so much that, when emperor Vespasian reach power, he invented a tax to levy the urine of public baths, the  urinae vectigal, a fee for which his own son Titus complained because its “disgusting” nature. The historian Suetonius tells us that Vespasian put a coin right under Titus’ nose and asked him if it smell of something, his son said no. Vespasian then said – Atqui ex lotio est (and it comes from urine) – leaving for the future the so-called Vespasian axiom, Pecunia non olet (Money does not stink), meaning that money is valid no matter where it came from. Vespasian’s name is still associated with public baths in some European countries: vespasiani in Italy, vespasiennes in France and vespasiene in Romania. By the way, author William Dietrich tells us in his novel “The Barbed Crown”, that Napoleon’s troops also collected urine to wash the soldier’s uniforms since, apparently, it is very good at eliminating blood stains. I am also sure that, somewhere in the world, the methods and ingredients of the fullones are still applied.

urinae vectigal, a fee for which his own son Titus complained because its “disgusting” nature. The historian Suetonius tells us that Vespasian put a coin right under Titus’ nose and asked him if it smell of something, his son said no. Vespasian then said – Atqui ex lotio est (and it comes from urine) – leaving for the future the so-called Vespasian axiom, Pecunia non olet (Money does not stink), meaning that money is valid no matter where it came from. Vespasian’s name is still associated with public baths in some European countries: vespasiani in Italy, vespasiennes in France and vespasiene in Romania. By the way, author William Dietrich tells us in his novel “The Barbed Crown”, that Napoleon’s troops also collected urine to wash the soldier’s uniforms since, apparently, it is very good at eliminating blood stains. I am also sure that, somewhere in the world, the methods and ingredients of the fullones are still applied.

Well, I hope we have learned something new today, at least that is my intention and I hope to come back son with another anecdote on the ancient world’s daily life. But, wait! Didn’t I say that urine was used for worse things? – Indeed, our Roman ancestors also used urine as mouthwash, to whiten their teeth. I leave it at that and remember the warning at the beginning, don’t try this at home, I am not responsible.